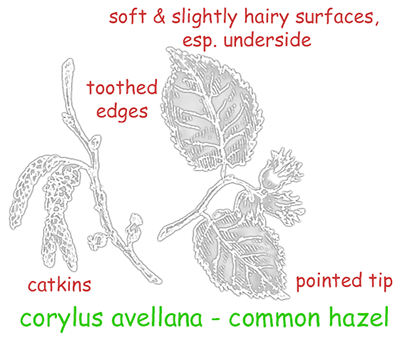

Corylus avellana (Hazel)

In Toll Wood:

The Hazel is relatively poor for long-term ecosystem services of sequestration, pollution control and sustainable drainage systems) but it is very important for woodland and hedgerow biodiversity.

The multi-stemmed habit leads to dense cover for nesting birds. The important contribution to biodiversity has led to our planting several hazels in our mixed planting for renewal of our boundaries project. Boundary management requires both habitat development and security. Hazel thrives on chalky soils.

Left to its own devices, hazels are multistemmed, growing to more than 5m in height in five to ten years and lives for around 80 years. To restrict that height and reduce shading of other plants, hazels should be coppiced in alternate years. In larger stands, a seven-year rotation of copicing creates complex, dense growth of high biodiversity value.

Coppicing hazels leads to hazel "stools" that live for hundreds of years, making it a valuable plantation tree.

Managing hazels in hedgerows is often done by mechanical flailing (or "fletting"). The 'violence' of this method is shrugged off by this vigorous shrub/tree. Commercially, the wood is used widely in crafts and as firewood.

In Irish and Gaelic mythology, the hazel is often thought to be a "tree of knowledge" - the nuts holding and aiding wisdom, inspiration and learning. Druids and others use the highly flexible wands for divination purposes. Hazels also have a reputation for inspiring poetry for those sitting beneath it.

Note that the filbert (Corylus maxima) is not native to the UK.

Biodiversity value: HIGH

Early flowering supports pollinator insects, edible catkins and abundance of nuts supports mammals and birds, fleshy leaves support sap sucking and leaf-eating invertebrates. The thick leaf-litter is also of significant biodiversity value. Hazels also fix nitrogen in the soil. Hazels are monoecious - flower and catkins appear on the same tree.

Around 150 invertebrates exploit hazels (suckers, chewers and borers). Add to that the mammals (mice, dormice, squirrels, and people), birds, and fungi and hazels stand out as a highly valuable part of woodlands and hedges in our countryside .

Mature hazels can 'rain' sticky honeydew - the exudations of huge populations of aphids that enjoy hazel leaves. This can attract sooty mold.

Leaf fall: Hazels generally lose their leaves late (Mid-to-late November), depending on first frosts. With climate change extending warm periods, holding onto leaves for longer makes sense as a survival mechanism. But, potentially more extreme autumn storms will also lead to timely shedding of leaves.