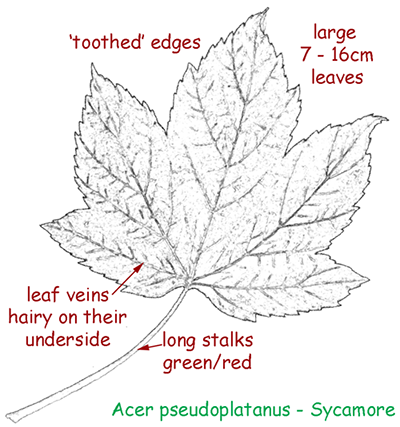

Acer pseudoplatanus (Sycamore)

In Toll Wood:

Whether sycamore is 'native' or not is debated. Classed as a 'pioneer' species, quickly able to colonise open or scrub land. Its winged seeds (samaras) spread easily, grows quickly and its very large leaves create dense shade that suppresses competition in the understorey and woodland floor. Unlike our native Field Maple, sycamore leaves are dog-toothed. There are several well-established sycamore and a great many saplings and invasive young trees that need to be removed to help sustainability of the rich mix of native apecies across the whole woodland. Sycamore trees are generally better suited to open or parkland planting.

Some sycamore are more difficult to thin than others! The image (above) shows that we have 'fused' elm and sycamore!

Where sycamore is removed, we will be clearer on where we have opportunities for succession-planting. This will be most important in the southern sector currently dominated by ash and struggling sycamore. With the possibility of ash die-back disease, mixed planting will be important if we are to repair 'gaps' in habitat for organisms that are currently dependent on ash.

Management principle: Allow selected young sycamore to grow for about twenty years (when they can start setting seed/samaras) before felling to allow newer sycamore to take over in providing biodiversity in dependent species. In particular, in the southern tip of Toll Wood, some sycamore must be retained against the day that ash die-back arrives as they share many dependent invertebrate species.

Biodiversity value: LOW/MEDIUM

In the 'right' place, sycamore can become massive, making them very good at fixing carbon. Their large leaves make the tree useful as part of a sustainable drainage system (SuDS). Their value in a woodland setting are LOW. It is host to a signicant number of leaf-chewers (32) but less so for sap feeders (11).

Leaf fall: Sycamores generally lose their leaves in mid-season (October/Early November), depending on first frosts. With climate change extending warm periods, holding onto leaves for longer makes sense as a survival mechanism. But, potentially more extreme autumn storms leaves them vulnerable to wind-throw or damage to limbs if leaves remain too long.